‘Stiva da morts’ – a community mortuary building and not merely a room or hall for viewing the deceased – expresses a particular attitude to an architectural task that is currently in growing demand throughout the region. Traditional burial rites that included viewing the deceased in his or her own home are steadily disappearing. More distance from the reality of death is wanted today and, because an increasing number of people die in old people’s homes or hospitals, they often no longer have a home in their village of origin, in the place where they might like to be buried.

The community mortuary building offers a special place for the rites of transition that occur before the funeral itself, one that symbolically, physically and in terms of its ambiance lies somewhere between the everyday life of a village and the sacral grounds of a church and cemetery. In fact, the community mortuary building is located next to the cemetery and is oriented to it, yet is still clearly outside of it. Like the surrounding residential buildings, it is built of wood and yet it is painted white and almost resembles a church. Its exceptionally powerful corner supports protrude into the space and recall both the pilaster columns of the church and the projecting walls of local houses. Its rooms emit a warm aura reminiscent of village parlours, albeit the wood here appears more solid and imposing, and has an unusual physical presence that conveys a feeling of strength and security. The almost rough-hewn solidity of this ‘Strickbau’ which is visible and palpable also in its interior, is alienated by means of a shellac finish that gives a matt shine to its surfaces, either honey-coloured or golden, depending on the light.

The main room of the ‘Stiva da morts’ is on the lower storey and oriented towards the village. Here, the mourners can gather and sit by the deceased. The upper storey offers a complementary, more intimate room, to which people might retire for a cup of coffee or to chat; just as in domestic funeral settings people retire to the kitchen to take some distance from the deceased and from formal, pre-funeral rites.

The building was constructed with a virtuosity that is nonetheless serviceable and quasi pragmatic. One can marvel at how the outer wall is hinged onto the inner wall: a means of surmounting the difficult problem – caused by the severe slope of the site – of building walls of different heights; or at how, on the upper storey, a considerable span width was bridged by suspending it from the double girder concealed in the roof construction. This is unimportant however. The construction design is not intrusive. It remains in the background.

LICENSING AND COPYRIGHT ACQUISITION: Search and view in jesusgranada.eu is free and any different use outside here must be authorized. If you are a publisher, journalist, publicist or manufacturer interested in use photos from this project on your magazine, book, company or marketing campaign, you need to acquire copyrights about needed photos. Fill this form to obtain conditions and fees of copyrights.

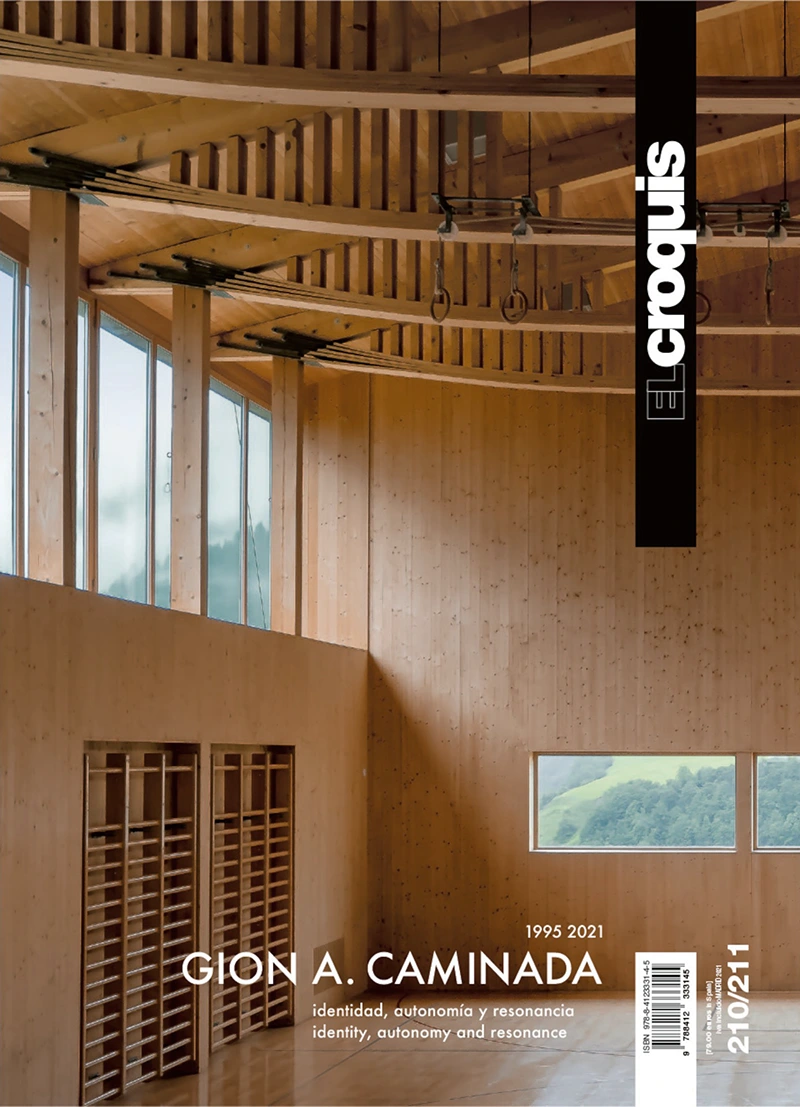

Commissioned by ‘El Croquis’ publishers:

El Croquis N. 210/211 Gion A. Caminada. Identity, Autonomy and Resonance.

Gion Caminada was born in Vrin, Switzerland, in 1957. After working as an apprentice carpenter in Vrin, he attended a school of applied arts in Zurich and an art school in Florence prior to completing his postgraduate studies in architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. He has had his own architectural practice in Vrin since 1986. In 1998 he was appointed Assistant Professor at the ETH Zurich, where he was Associate Professor of Architecture and Design from 2008 to 2020. Since 2020 he has been a Full Professor of Architecture and Design at ETH Zurich.

Semi-hard cover – 376 pages

24 x 34 cm – 2,5 Kg

ISBN 8412333144